What is the future of capitalism?

Last week, I discussed how capitalism is a natural way for many of our desires to organize economic activities, though leaving important other desires out in the cold. The philosophical work to come up with alternatives to capitalism appeared, in the end, to be a practical dead end, however appealing to idealists. But what comes next? Once we have settled on the mixed political / economic system that is the rule over most of the modern world, how can we envision it serving humanity into the future? Is it sustainable?

The answer to that is: obviously not. We have far higher population, and use far more resources than the earth can supply sustainably. We might blame capitalism, but that is just the ugly packaging covering our own desires. There was a nice article in the NYRB recently about "degrowth communism", promoting the ideas of Kohei Saito, another provocative self-labeled Marxist. It makes of Marx some kind of prophet of green, which frankly could hardly be farther from the truth. Marx wanted workers to own the means of production so that they could all share in the fruits of modern technology, not to make them return to the idiocy of rural life. So, while degrowth is an important idea, its connection with Marxism is specious, other than the catastrophic degrowth unintentionally induced by the various implementations of Marxism through the last century.

If we excercised our wisdom, we would desire, first and foremost, a sustainable form of life. Unfortunately, our technologies and forms of pillaging the earth have ranged so widely by this point that we hardly have any idea of the harms we are causing and the shortages that are building up. Who would have predicted that plastics and forever chemicals would turn into a growing plague? Who has the answer to climate change? The key thing to realize, however, is that we have the power. We do not need a revolution overturning capitalism, because we have the state. The state can regulate, it can nationalize, it can utility-ize, it can crush companies or create them. It can make the rules and change the rules. It is through the state that we can express our larger desires for sustainable and decent living.

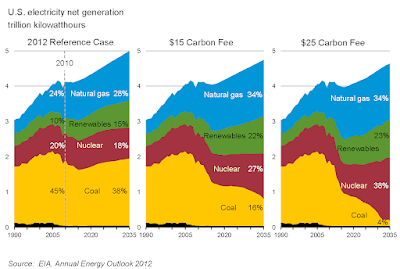

For example, states can (and have) set up a carbon tax to move the transition away from fossil fuels. California has done so, as have many other countries. Just because we in the US are at a corrupt and mean political moment where short-term (at best) thinking rules the roost does not mean that people's deeper and longer-term interests will forever remain submerged. Indeed, this moment has provided an instructive (if appalling) window into how powerful the state can be.

The article cited above also maintains that growth is inherently tied to capitalism, and that degrowth requires a revolution of some kind. Again, I beg to differ. Capitalism simply is a way to satisfy our desires. If we want to live simply, it will still serve us. Whether growing or contracting, capitalism marches on doing its best to satisfy our desires. Companies compete for business and growth, but there are plenty who have stable business models, such as, to take one example, the toothpaste business.

More interesting is the popular revolt against growth that is expressed in declining birth rates. All over the modern economies, people are having fewer children, and causing a great deal of head-scratching and alarm. Is this due to the death of patriarchy? A fear of the future? The death of boredom? I think it has a lot to do with the fundamental contraction of our frontiers and a sense of limits. After a couple of centuries of breakneck growth, when large families were common and there were always new territories to occupy, we in the US hit the ceiling in the 1970s. Cities stopped growing, housing construction slowed, zoning enforced stasis. The expense and complexity of raising children in this environment grew as well, becoming subtly more competitive than cooperative.

So, growth is slowing already, but not enough to save us from extreme ecological harms. We do need a more conscious degrowth strategy, encompassing accommodation of lower population, slowing down of lifestyles in some regards, strong movement through the sustainable energy transition, expanding natural habitats instead of degrading them. In all these issues, capitalism is not the problem. The problem is figuring out what we really want. In Europe over the centuries, there was a gradual transition from building with wood to building with stone. Which is to say, the value of sustainability gradually won out over wasteful short-term solutions. We need to start building in stone, metaphorically, thinking of the next hundred and thousand years, not just our own brief lifetimes.

- Bearing witness to the unconstitutional court.

- Krugman points out that Brazil is way ahead in crypto... specifically their central bank coin, Pix. In the US, banks, crypto, and Republicans are ideoidiotically opposed.

- Continuously unconstitutional.

- Is nothing sacred?